By Lawrence MowerTimes staff

Alex HarrisMiami Herald staff writer

Published Aug. 12|Updated Aug. 15

TALLAHASSEE — Florida’s crumbling homeowners insurance market is exposing one of the state’s long-running flaws: its reliance on a single company to certify the majority of the state’s insurers.

For the last few weeks, state regulators and Gov. Ron DeSantis’ administration have been scrambling to contain the fallout after the state’s primary ratings agency, Ohio-based Demotech Inc., warned of downgrades to roughly two dozen insurance companies, according to the state.

The downgrades would have triggered a meltdown of the state’s housing market, a pillar of Florida’s $1.2 trillion economy. Without the ratings, a million Floridians could be left scrambling to seek new insurance policies, possibly triggering a housing crisis in the middle of hurricane season and months before the November election.

State regulators believe they have staved off a disaster, at least temporarily, but the episode has observers questioning how it was handled and how the state could be so reliant on a single company few have ever heard of.

“If this was a movie title, it would be ‘The Sum of all Fears,’” said Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, who has been warning for years that the state’s property insurance market was heading toward collapse.

The DeSantis administration cobbled together a short-term fix to allow insurers to stay afloat by using state-run agencies to back them up. And it went after the ratings agency, Demotech, and its president and co-founder, Joe Petrelli, calling it a “rogue ratings agency” and urging federal officials to disregard the company’s actions.

Ghosts of Hurricane Andrew

The drama is just the latest problem as the state experiences its biggest insurance crisis since Hurricane Andrew in 1992.

In the last two years, more than 400,000 Floridians have had their policies dropped or nonrenewed. Fourteen companies have stopped writing new policies in Florida. Five have gone belly-up in 2022 alone. The record, set after Hurricane Andrew’s devastation, is eight in one year.

The latest casualty was Coral Gables-based Weston Property & Casualty, which leaves 22,000 policyholders — about 9,400 in South Florida — scrambling to find new insurance companies.

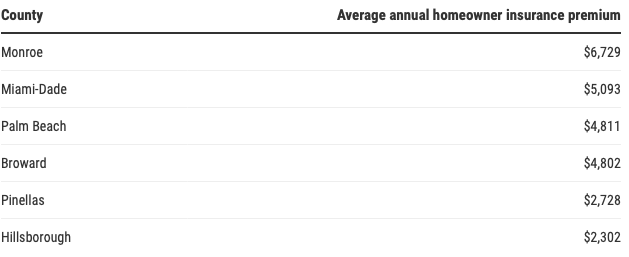

Costs also have skyrocketed. In 2019, when DeSantis was sworn in, Floridians paid an average premium of $1,988. This year, it’s now $4,231, triple the national average, according to an Insurance Information Institute analysis.

The storm reshaped Florida’s insurance landscape, forcing several companies out of business and others to flee the state. With homeowners struggling to find coverage, the Legislature created the state-backed Residential Joint Underwriting Association — essentially a forerunner to today’s Citizens Property Insurance — to insure homes that couldn’t be covered by private carriers.

The program quickly became one of the largest insurers in the state, and concerns grew that it was taking on too much risk. State officials provided incentives for companies to take over its policies, and a number of new, smaller insurers got in line.

The new insurers faced a problem, however: They were unable to get a financial stability rating from a qualified ratings agency. Homeowners with federally backed mortgages, such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are required to have highly rated property insurance companies protecting them.

State insurance and banking regulators, plus Fannie and Freddie, looked to various ratings agencies for help. Only Demotech was willing to rate the new insurers. The company, based in Columbus, Ohio, was founded in 1985 by Petrelli and his wife, Sharon Romano Petrelli. Its “A” rating was approved by both Fannie and Freddie.

Since then, Demotech has been the primary ratings agency for Florida-based insurers, which dominate Florida’s market and which pay Demotech to rate their financial strength. Although other ratings agencies, such as New Jersey-based AM Best, provide ratings for some insurers, no one has stepped in to compete with Demotech.

Without Demotech, Florida would not have an insurance market, said Kevin McCarty, the state’s insurance commissioner from 2003 to 2016.

“Regardless of whether you agree with them, they serve an invaluable service to the state of Florida and across the wider economy,” McCarty said.

‘We never got a phone call’

Florida’s reliance on smaller insurers has caused homeowners to ride out a series of booms and busts ever since.

Smaller insurers are mostly able to survive Florida’s hurricanes because of reinsurance — essentially, insurance for insurance companies. When a storm hits, an insurer might be on the hook for a few million dollars, while the reinsurer pays the rest.

But the smaller companies in particular are vulnerable to increases in the cost of reinsurance. A series of storms in 2004 and 2005 wiped out a number of insurers and drove up the cost of reinsurance, putting firms in a pinch. Several have gone out of business due to mismanagement or incompetence.

In the last few years, insurers and state regulators have blamed excessive lawsuits for their woes, and Petrelli has been an outspoken critic of the Legislature’s inaction to curb litigation.

He has cited statistics from Florida’s insurance commissioner that from 2016 to 2019, Florida accounted for between 7.75% and 16% of the nation’s homeowners’ claims, but between 64% and 76% of the nation’s litigated homeowners’ claims. Critics say insurers’ problems are more complicated.

DeSantis called a special session of the Legislature in May to pass insurance reforms focused on stabilizing the market and reducing lawsuits, but Petrelli said it wasn’t enough.

On July 18 and 19, Demotech sent private notices to at least 17 Florida insurers, according to state officials — almost half of the companies it rates in Florida — warning that the insurance environment was worsening and that without corrective action, the companies faced a ratings downgrade. (Demotech has not said how many companies received the warnings.)

A ratings downgrade of that magnitude would create shockwaves. Fannie and Freddie back about 62% of all residential mortgages, according to the Florida Association of Insurance Agents.

Demotech’s “A” rating and above, which indicates a 97% certainty a company could afford all the claims from a 1-in-130 year hurricane, is approved by Fannie and Freddie, while its “S” rating, the next step down, is not.

A reduction from an “A” rating would force homeowners to find a new insurance company — and fast. Otherwise, the bank holding the mortgage could “force place” a homeowner with whatever insurance company they can find, which is usually far more expensive and offers less protection. That could include placing a homeowner with what’s known as a “surplus lines” insurer, which doesn’t need state approval for their rates. They can charge whatever they want.

“Getting force-placed insurance is terrible for a homeowner. You’re paying double the premium and getting half the coverage,” said Paul Handerhan, president of the consumer-oriented Federal Association for Insurance Reform, based in Fort Lauderdale.

Many homeowners would likely end up with Citizens, placing more risk with the state-run insurer that already covers nearly 1 million policies. (Its peak was 1.4 million, in 2011.)

Demotech, in large part, blamed the Legislature’s inaction for the changes.

“In Florida, the unwillingness or inability of the legislature to address longstanding disparate, disproportionate levels of litigation, and increasing claims frequency has resulted in a level of dysfunction that renders our previous accommodation inapplicable,” several of the letters state.

DeSantis’ office coordinated a swift and public attack on Demotech.

In letters to federal housing authorities on July 21, Chief Financial Officer Jimmy Patronis called Demotech a “rogue ratings agency.” Florida Insurance Commissioner David Altmaier wrote that it was an example of “inconsistent, monopolistic power of a select rating agency and is trying to exert coercive influence over Floridians and policymakers in an effort to thwart public policy according to its own opinions.”

Even U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio waded into the fray, asking the Federal Housing Finance Agency to reexamine its dependence on Demotech.

Petrelli said he had no warning and no conversations with state officials before the letters were sent to federal officials and the news media. He said the correspondence with the companies was the normal course of business, part of regular, ongoing conversations with companies about their financial status that they’ve been doing every quarter since 1996.

The level of rancor was “unprecedented,” Petrelli said, but it did not change how it rates companies. In recent weeks, four companies have had their ratings downgraded and four, including Weston, have had their ratings withdrawn.

“It did not deter us,” Petrelli said.

Mark Friedlander, communications director for the industry-backed Insurance Information Institute, said the response was unlike anything he ever had seen. Ratings agencies are supposed to be neutral third parties that rate companies without influence, he said.

“It was definitely, in our opinion, stepping over the line,” Friedlander said of the state’s response.

On the other hand, Petrelli “has pushed himself further into the limelight by publicly engaging in political theater,” the Florida Association of Insurance Agents said in a memo distributed by the Office of Insurance Regulation.

The association’s memo wondered whether the state’s insurers should move on from Demotech. It raised longtime criticisms that Demotech often downgrades a company just days before it goes insolvent.

“That often begs the question, ‘Does a Demotech rating mean anything or provide the intended peace of mind to agents, consumers, and lenders?’” the memo stated.

Petrelli said companies keep their “A” rating as long as possible precisely because the “S” rating is not accepted by Fannie and Freddie, despite Demotech’s numerous attempts to get them to accept it.

When a company gets an “S,” he said, “unfortunately, they drop off the edge of the cliff.”

A ‘very elegant’ solution

Notably, the Office of Insurance Regulation’s letter did not dispute that Florida insurers were failing. The office has its own watch list of 27 companies under “enhanced monitoring.”

Patronis’ letter suggested insurance companies needed to find a new rating agency, but Friedlander said that likely wouldn’t help. The New Jersey firm AM Best has stricter requirements than does Demotech, he noted.

Six days later, the state announced a solution should the companies have their ratings downgraded.

Florida’s plan is to let insurance companies that are financially stable, but just missing that “A” rating from Demotech, to keep operating and covering people’s policies.

If they go under, homeowners’ claims would be covered by the long-running state program known as the Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, which covers the first chunk of claims for any failed insurance companies. Citizens would foot the bill for anything over the limit of $500,000 for homes and $300,000 for condo units.

Handerhan called it a “very creative, very elegant, very consumer-centric” solution.

But will it satisfy the federal mortgage holders?

Despite repeated emails and calls over the last week from the Times/Herald, representatives from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac didn’t offer an answer. The Florida Housing Finance Agency didn’t respond to Rubio, either, according to his office.

An Office of Insurance Regulation spokesperson said they’re “confident” the solution will be acceptable.