Jamie Lafollette found out State Farm was dropping her policy from reading the news.

After she saw a story about the insurer pulling out of Santa Cruz County, her longtime home, she called her agent to confirm that her plan would lapse — setting off a desperate search for a replacement policy that is ongoing.

“Our first quote came in at over $10,000 a year, and that was bare bones coverage,” she said. “And then I kept pressing, contacting other brokers … contacting all these weird companies you’ve never heard of.”

But those quotes were even higher, coming in between $17,000 and $25,000, she said.

Lafollette lives near Soquel, which lies near Monterey Bay and its picturesque view of the Pacific Ocean. The location’s trade-off is the forest that surrounds her home, bringing with it the ever-growing threat of wildfire.

It also makes homeowners insurance essential. But the prices Lafollette was quoted are well out of her budget.

“I’m at the point where I don’t know if I can keep my home,” she said.

According to State Farm, such cases of cancellation amounted to only 2 percent of policies in the state. But it still means homeowners like Lafollette have few good options.

It’s also a problem for a growing share of Americans.

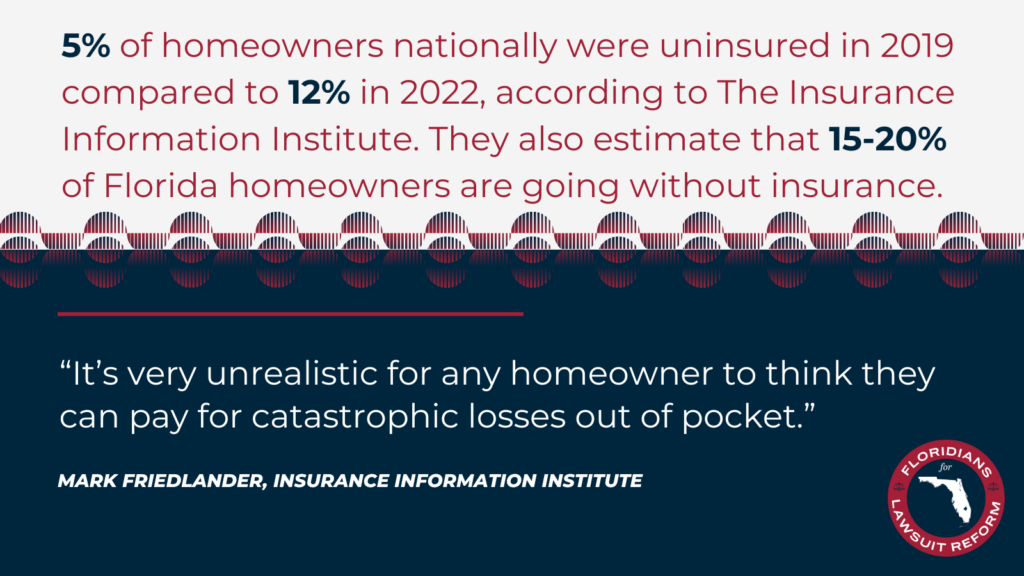

One 2023 estimate, released by the industry group Insurance Information Institute, concluded that 12 percent of homeowners had no insurance in 2022, up from just 5 percent in 2019.

Another more recent study, released by the Consumer Federation of America in March, reported a lower share of uninsured — 7.4 percent — but that estimate is based on 2021 data from the American Housing Survey, which the Census Bureau conducts every two years. The organization will revise that share upward once 2023 numbers come out, said the CFA’s director of housing, Sharon Cornelissen.

Most uninsured homeowners are those who have paid off their mortgage and are no longer required to have insurance. Among those who own their home outright, the CFA estimates roughly 14 percent are uninsured, with low-income and minority homeowners especially at risk. Among mortgage holders, only 2 percent opt to go without coverage.

Experts say this trend is driven by the escalating threat of climate change — which has forced insurers to make larger and larger payouts — and skyrocketing housing prices. Both trends are pushing the cost of policies up. On average, home insurance policies rose 11.3 percent in 2023, according to S&P Global.

Compounding the problem, some insurance providers are pulling out of disaster-prone areas as a result of rising payouts — leaving former policyholders with fewer and more expensive alternatives.

Homeowners like Lafollette say they’re not going without insurance by choice. When their policies are discontinued, they’re unable to find an alternative.

Such a decision carries great risk, said Mark Friedlander, director of corporate communications for the Insurance Information Institute. “It’s very unrealistic for any homeowner to think they can pay for catastrophic losses out of pocket,” he said.

The uptick in homeowners forgoing coverage is especially striking given that lenders require mortgage-loan applicants to carry insurance.

In extreme cases, a homeowner’s decision to stop paying for a policy can be considered a form of default and even lead to foreclosure, Friedlander noted.

A more common route is that a bank will simply select a plan and impose the costs on the uninsured homeowner. But that coverage is unlikely to cover natural disasters, Cornelissen said.

Meanwhile, companies like State Farm have made headlines after announcing that they would not renew policies in wildfire-prone counties like Santa Cruz. In other states, like Iowa, homeowners are finding that their insurance companies are abandoning them as climate change increases the possibility of natural disasters.

Those companies say they can no longer make a profit insuring homeowners in those regions. The problem is not just cost. Reinsurance companies, like Swiss Re, that provide insurance to insurance providers in the event of a catastrophe are also charging more, raising costs for companies like State Farm, said Marco Giacoletti, assistant professor of finance and business economics for the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business.

At the same time, agencies in some states, including California, Colorado and Florida, are authorized to approve rate increases — and these regulators don’t always let insurance providers pass all their costs to consumers, Giacoletti said.

In addition, in California’s case, insurance companies must use historical data, rather than forward-looking models, when they price insurance plans. That means their policies may not reflect the actual risk they’re supposed to hedge against, he added.

“With climate change, you want to use forward-looking models,” Giacoletti said. “Insurance companies are not able to price their plans properly,” leading to sustained losses after climate-driven disasters.

In California’s case, the insurance commissioner in March approved a rate increase of 20 percent, as requested by State Farm.

Homeowners who have been dropped from their policies have few substitutes in an increasingly expensive market.

Lafollette’s husband is a disabled veteran, and the family has developed a support network in Santa Cruz, which makes moving a less-than-ideal option. For now, their community has invested in expensive upgrades intended to reduce fire risk, with the hope that it can persuade insurance companies to continue their policies.

“It was very hard to convince our community to buy in to do these things,” Lafollette said. “[But] none of us can afford to lose our insurance. And we thought if we do these things, we won’t lose our insurance.”

The statistics don’t fully capture the extent of homeowners’ dilemma.

Kathleen Haughton, for example, moved to California’s Butte Valley from Paradise after her hometown was destroyed in 2018’s devastating Camp Fire.

She needed a loan to rebuild her house, which meant buying insurance. Her cheapest option was $7,000 a year for a California Fair plan, which offers insurance to people who can’t buy from major companies.

Priced out of that option, Haughton bought a $1,200-a-year plan that doesn’t cover natural disasters — and hopes that the Camp Fire was a once-in-a-lifetime catastrophe.

“I figured if I lose everything again, that’s God’s plan,” she said.

Experts see the experience of homeowners like Haughton and Lafollette as a grim harbinger of things to come with a heating planet.

“People are really feeling climate change,” said Emily Schlickman, an assistant professor of landscape architecture and environmental design at the University of California at Davis who studies climate adaptation. “Not being able to get insurance is one of the first ways we’re coming to terms with our new reality,” she said.

Patrick Cooley is a freelance journalist who previously covered agriculture and commodities for The Messenger and environmental and agricultural issues for the USA Today Network.