The average home insurance policy in Florida is $6,000 annually, almost four times the national average. And the skyrocketing rates show no sign of letting up.

This story is part of an ongoing series about Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ policies and how they impact the people in his state. For full coverage, click here.

ORLANDO — Floridians today are concerned with a multitude of issues ranging from education to immigration to abortion. But on the ground, there’s a comparatively mundane subject at the forefront of residents’ minds: property insurance.

Basically, premiums are skyrocketing. “As people get their renewals, they’re cringing to open up the letter from the insurance company, because either there’s a ridiculous premium increase, or they’re being dropped,” says Anna Eskamani, a Democratic state legislator representing part of Orlando. “That has been a constant pattern, and there’s no end in sight.”

The decreasing affordability of property insurance in Florida has reached a crisis level, making it the most pressing economic issue for many residents. There are unique roots to the crisis in Florida, largely a proliferation of litigation and a surge in fraudulent claims—all with the backdrop of hurricanes making the market increasingly risky. But finding ways to rapidly lower costs for consumers is tricky.

The average cost of a home insurance policy in Florida today is $6,000 a year, compared to the national average of $1,700. It’s consistently rising, up 40% this year alone, which is four times the national increase. If trends continue, the average rate could be $8,400 next year. “Florida consumers are suffering severe pain when it comes to finding home insurance and affordable home insurance,” says Mark Friedlander, director of corporate communications for the Insurance Information Institute, a nonpartisan association that helps consumers understand insurance.

What’s causing the surge in premiums?

Florida is a risky market to begin with. It’s ground zero for hurricanes: 40% of hurricanes in the U.S. have hit Florida, and last year’s Hurricane Ian, which struck the Fort Myers area and killed at least 161 people, will likely be the second-largest insured loss on record, at $63 billion, second only to Katrina.

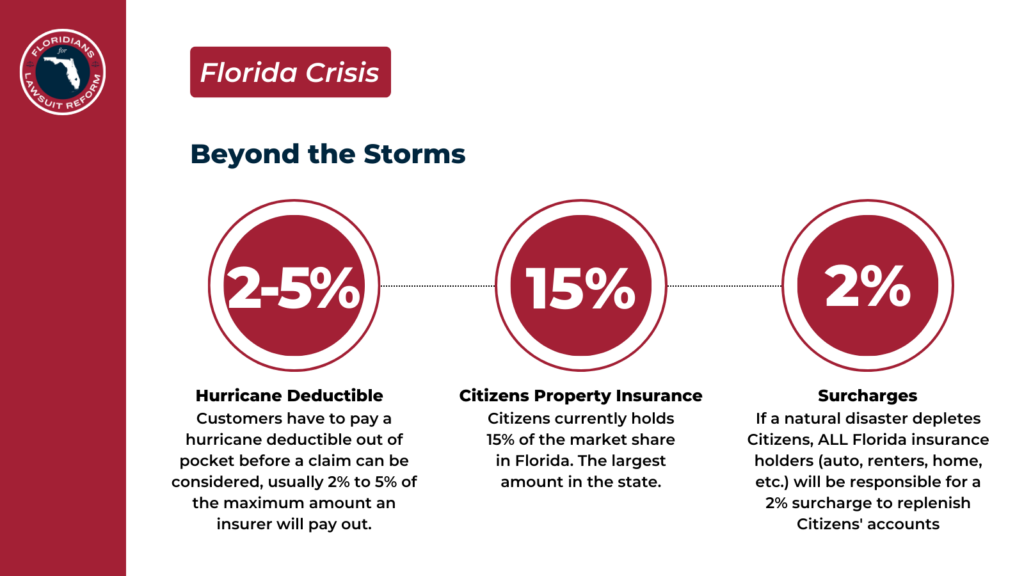

This environment already makes insurance expensive; since 1992’s blistering Hurricane Andrew, customers have to pay a hurricane deductible out of pocket before the claim even kicks in, usually 2% to 5% of the maximum amount an insurer will pay out. On a $400,000 policy, that’s a deductible of up to $20,000. “Many homeowners who suffered major losses from Hurricane Ian were not able to afford their deductible,” Friedlander says.

But two man-made factors have compounded the issue over the past few years: litigation and fraudulent claims. “Those are the key features that make the Florida scenario different,” says Melanie Gall, assistant professor at Arizona State University and codirector of its Center for Emergency Management and Homeland Security.

Floridians have filed the most property insurance litigation in the entire country, by a wide margin: 79% of all U.S. lawsuits were in Florida, even though the state represents only 9% of total claims. The rate is almost 30 times that of California, home to the most property insurance policies. The state has been friendly for plaintiffs, with a “one-way” attorney fees policy for the past decade, meaning that if the plaintiff wins, insurers are liable for all attorney fees. “This was really the springboard to all these mass-volume lawsuits,” Friedlander says.

The litigation comprises both legitimate lawsuits, for denial of claims, and frivolous lawsuits. Much of the latter comes from a surge in roof replacement scams, in which duplicitous contractors go door-to-door informing residents that they need their roofs fixed and that the repairs can be done for free or at a low cost. These contractors then file claims to insurers ostensibly on behalf of the residents, often asking for exorbitant reimbursements that get rejected because they’ve laid brand-new roofs for simple wear and tear. What’s more, the contractors often sue the insurers for the denial. “Homeowners are being scammed,” Friedlander says. “They’re signing over and not really understanding the implications.”

How does all of this affect the market?

As well as driving up prices for consumers, the situation is pushing insurance companies out of Florida. Seven declared insolvency from February 2022 to February 2023; others left voluntarily, and still others stopped writing new policies. Long before State Farm and Allstate announced they were halting new business in California, as they did last week, the national insurers were all but gone from Florida. State Farm is the only top-10 insurer still operating in the state; the rest are mainly regional, independent firms.

The soaring premium rates have driven many homeowners to Florida’s insurer of last resort, state-backed Citizens Property Insurance Corp. It’s mandated to charge the lowest fees, about 40% less than the average private insurer; the average rate for customers was $3,200 at the end of 2022. Citizens now has the biggest market share, at 15%. “That’s a really bad thing,” Friedlander says. “Your backstop insurer is not supposed to be your largest insurer. They have this very large increased risk, and they’re not charging enough to cover that risk.”

A huge natural disaster could deplete the company’s reserves. Friedlander says that could trigger rate increases for Citizens customers of up to 45%, as well as annual surcharges of around 2% on all buyers of insurance, including home, renter, and auto. “Every Florida consumer would be on the hook to help replenish the funds of Citizens,” Friedlander says.

And in a state like Florida, such a disaster isn’t unlikely. Studies show hurricanes will get more frequent with climate change. So far, none of the most devastating hurricanes have hit major cities, which could be catastrophic. When Hurricane Andrew struck Homestead, 30 miles from Miami, Maria-Elena Lopez, vice chair of the Miami-Dade Democratic Party, says her Miami neighborhood’s trees all collapsed, and power was out for a month. “We suffered the consequences, and the hurricane was nowhere near us,” she says. In Downtown Miami, with its high-rise condos: “You get a hurricane through there, and those buildings will fly.”

How has the state addressed the crisis?

The Florida Legislature has passed various bills in recent months addressing the crisis, mainly focusing on propping up the insurance companies. In December, Governor Ron DeSantis signed a package that will force some policyholders off Citizens and onto private alternatives; additionally, it will require holders of new Citizens policies to buy flood insurance, even those who don’t live in flood zones. It sets up a $1 billion fund for reinsurance (for insurers to insure themselves, so they don’t deplete capital), and scraps the one-way attorney fees to reduce litigation.

The bills don’t focus on lowering premiums, and in fact may hike them in the short term. But Friedlander says this market stabilization was necessary. They need to keep insurers in the state, because if they go, it will leave fewer choices for consumers and ultimately push prices even higher. In the meantime, it remains to be seen whether the action will curb costs. “Nobody could promise when this is going to improve,” he says, noting that rates are still likely to increase year to year.

DeSantis’s political opponents disagree about the effectiveness of the action. Eskamani says it only bolsters the insurance industry and doesn’t represent the needs of constituents. (A recent report also claimed that the insurance industry has donated $3.9 million to DeSantis PACs since 2018.)

Some of Eskamani’s Democratic colleagues proposed freezing or capping premiums. But experts say mandating lower rates would either force insurers out of business or result in them leaving voluntarily. Generally selling one-year policies, they have the luxury to come and go from states as they please, Gall says. “If they cannot turn a profit because they can’t raise premiums,” she says, “why would they take on the risk of staying?”

What happens next?

In recent days, there has been some pro-consumer legislative action. DeSantis signed a rare bipartisan package of bills in May that firms up insurer accountability and regulation. Among other things, the bills require insurance companies to submit their claims-handling processes to the state’s regulators, and bar insolvent companies from taking on new policies. In addition, they prohibit insurers from amending damage reports, a practice that came to light in a Washington Post investigation, which found that many companies secretly downgraded their descriptions of home damage after Hurricane Ian in order to reduce payouts to homeowners. Some cut claims by more than 80%.

In addition, an initiative called My Safe Florida Home will help residents pay for home resilience against storms in the form of secure roofing, storm shutters, and hurricane clips, which can drive down premiums. It will provide homeowners with matching grants for up to $10,000, whereby the state would give $2 for every $1 put toward mitigation projects. That’s a good policy, deems Cicely Hodges, housing policy analyst at the Florida Policy Institute, but she says the state could help lower-income residents with even more cash.

But going as far as actually subsidizing premiums for consumers is “tricky business,” Gall argues. This can make the region appear less risky than it is, attracting more people into an already booming state, which is building homes in hurricane hot spots at a historic pace. “The risk does not go away,” Gall says. “The premium should reflect the risk that you’re taking on by living in this location.”