By Ellen Milligan and Katharine Gemmell | November 16, 2021

Hedge funds, private equity and sovereign wealth funds are piling billions into the outcome of high stakes court cases at a faster rate than ever before.

Litigation finance — the practice of paying legal fees up front with a promise to share in any eventual payout — soared to a $39 billion global industry in 2019, according to law firm Brown Rudnick. It’s being used to fund everything from Russian oligarch’s divorces to take on banks in fraud suits. And now regulators are asking whether there’s enough oversight.

“More companies than ever before are exploring how legal finance can help their bottom line,” said Jack Neumark, head of Fortress Investment Fund LLC’s legal assets business. “We lose money if the claims we fund are unsuccessful, so we only finance claims that are supported by strong evidence and the law.”

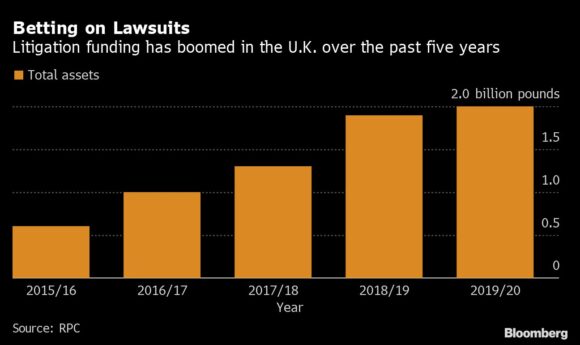

In the U.K. the sector saw record flows of money last year of 2 billion pounds, up from a little over 500 million pounds ($669 million) in 2016, according to data from law firm RPC. And that growth is showing no signs of slowing. The reality is though, that the real size of the market isn’t known because of a lack of transparency and disclosure across the sector. Omni Bridgeway Ltd., a public Australian funder, estimates a $100 billion global “addressable market.”

D.E. Shaw & Co., Elliott Management Corp. and TowerBrook Capital Partners are among those who have who’ve gotten in on the action. Litigation financier Burford Capital Ltd. scored big with a $103 million return from a divorce after backing the ex-wife of a Russian oligarch after she sought to recover a 450 million pound award that ended in a 135 million pound settlement.

Burford has a $4.8 billion current investment portfolio, up from $4.5 billion at the end of 2020. Last year, it made $758 million in new commitments to commercial legal assets, according to a client update. The stock is up 15% this year.

Aside from the Russian divorce settlement, litigation financing has been used in the U.K. to fund Amanda Staveley’s losing bid to recover 660 million pounds from Barclays Plc and a failed class-action privacy suit against Alphabet Inc’s Google. In the U.S., Bench Walk Advisors LLC has been linked to cases including for dating app Tinder against its parent company Match Group Inc.

“There is plenty of money available through the hedge funds for the right opportunity,” said Malcolm Hitching, a partner at London-based law firm Macfarlanes LLP. “The hedge funds love it because it’s non-correlated — they can get their arms around the risk.”

Proponents of litigation funding say it’s an important way of ensuring lawyers get paid and helps to allow individuals or firms with less resources to be able to afford costly lawsuits.

But critics say it can leave investors with a bigger slice of the pie than the claimants. European Union lawmakers are reviewing the need for rules for third-party litigation funding, while in the U.K. the industry is currently self-regulating.

In the U.S., the Justice Department said last year it was looking into disclosure of third-party litigation financing in some cases, in response to legislation. The department has brought criminal charges this year against several litigation financiers, including one who double-pledged investor funds and one who allegedly recruited defendants for staged trip-and-fall cases.

Litigation funding is seen as a neat way to diversify investments away from stock market instability, especially in hard times, such as the Covid-19 pandemic. On average, funders receive around 3 to 4 times their invested capital plus recovery of the legal costs if the case is won, according to Brown Rudnick.

Since forming its litigation funding arm in 2013, Fortress deployed more than $4 billion into a “diverse pool” of legal assets globally. It currently has 20 employees on a dedicated team.

Despite the clear upside if an investment pays out the risks abound.

Investments are difficult to sell out of, cases often take years to resolve and the risk of losing a suit is high. If a case isn’t successful, investors often get nothing back and are left to pay millions in legal costs, sometimes also for the opposing side. Even if a case is won, often the amount the court awards can fall below expectation.

The appeal is “partly the return profile because the headline returns are attractive” but “it’s not a cookie cutter asset class — cases can go wrong,” said Neil Purslow, co-founder of litigation funder Therium.

That’s why funders build a portfolio of diversified cases to spread the risk, similar to how private equity works, he said. One of the firms’ investors includes a sovereign wealth fund.

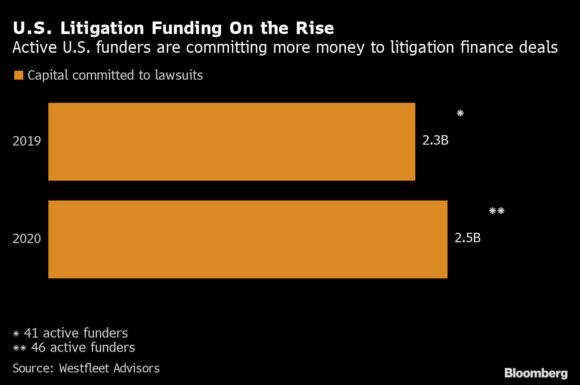

A survey of 46 U.S.-based funders from brokerage firm Westfleet Advisors showed they had a combined $11.3 billion in assets under management in 2020, an 18% increase from the previous year.

Litigation finance is set to rapidly grow in the next five years, the market will see “even more new types of funders, new types of claims being funded and the development of a secondary market,” said Elena S. Rey, partner at Brown Rudnick.

–With assistance from Roy Strom.